Polio, often referred to as “The Crippler,” is a disease that has left its mark on history, causing widespread fear and devastating consequences for those it touched. This viral disease primarily affects the gastrointestinal system, often causing little harm at first. However, when the poliovirus spreads beyond the gut and into the bloodstream and nervous system, it can lead to paralysis and, in some cases, death. This article delves into the history of polio, its impact on individuals and societies, and the long and difficult journey toward a global vaccine.

Introduction to Polio

Poliomyelitis, more commonly known as polio, is caused by a virus that spreads primarily through oral-fecal contact. The disease can be relatively harmless when confined to the digestive system, but if the virus reaches the nervous system, it can lead to paralysis. This paralysis most often affects the limbs but can also impact the muscles that control breathing and swallowing, putting the patient’s life at risk.

The first signs of polio can appear as a mild illness, but when the virus attacks the spinal cord, it can damage motor neurons, disrupting the connection between the brain and muscles. The result is muscle weakness or paralysis, which can leave victims unable to move, breathe, or swallow without assistance. The most severe cases are often associated with “bulbar” polio, where the patient’s respiratory muscles are paralyzed, and the need for artificial respiratory support becomes urgent.

Video

Watch this powerful video about a polio survivor’s story, The Man in an Iron Lung. Discover the struggles and resilience of living with polio.

The Spread of Polio in the Early 20th Century

Polio has existed for centuries, but it became a significant public health concern during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Ironically, as public hygiene and sanitation improved in industrialized nations, the disease began to spread more rapidly. This was partly because fewer infants developed natural immunity due to better hygiene practices, leaving a vulnerable population that could be infected by the virus.

The disease became increasingly prevalent during the postwar era, particularly in small towns and suburban areas experiencing a baby boom. This new generation of children, along with young adults, were more susceptible to the poliovirus, as it had a greater chance of entering their nervous systems and causing permanent damage.

Despite the advancements in modern medicine, the medical community struggled to understand how the disease spread and how it could be prevented. The polio epidemics of the early 20th century overwhelmed public health systems, and it wasn’t until the late 1940s that significant breakthroughs in scientific research began to offer hope.

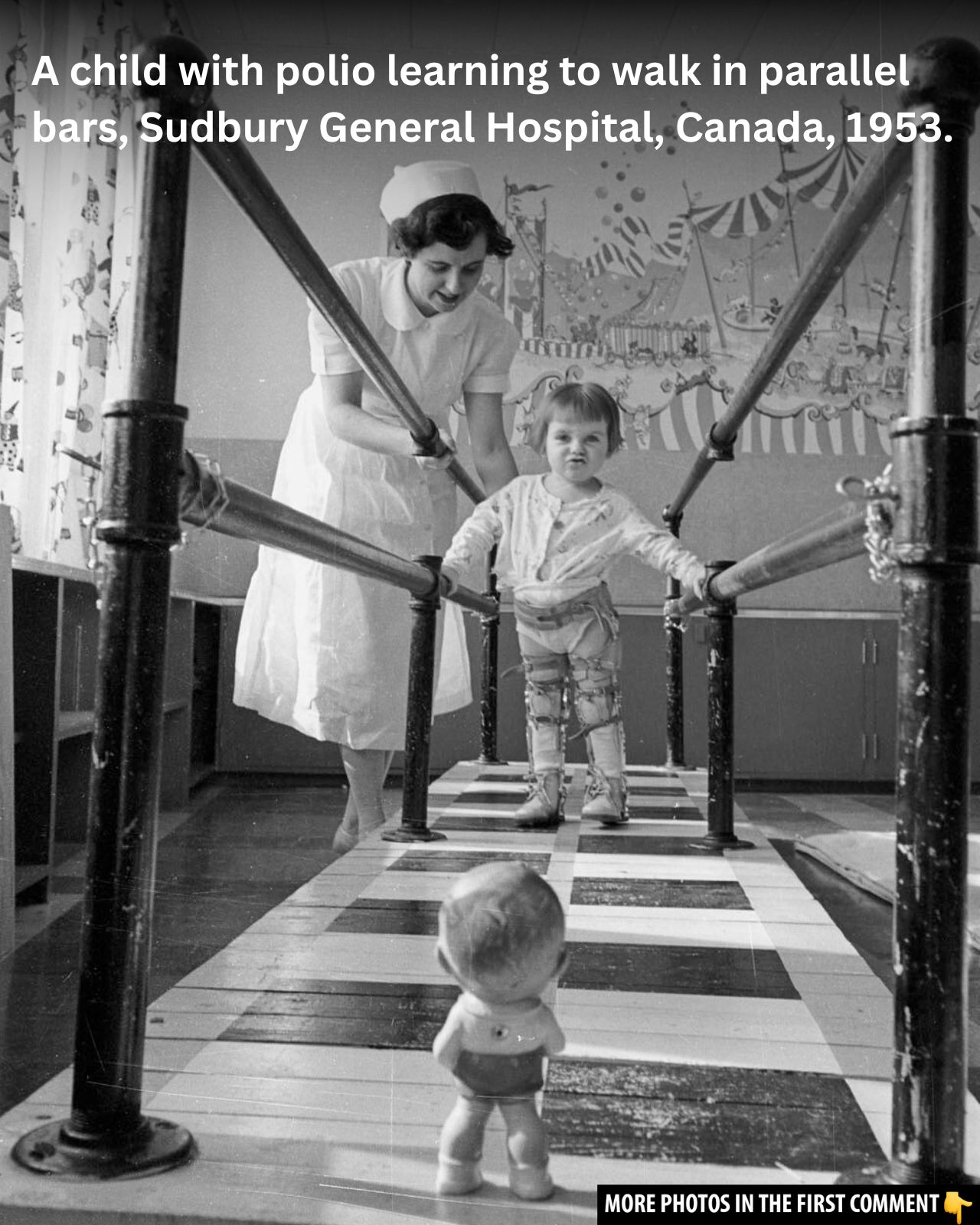

Personal Perspectives on Polio: Stories from the Epidemic

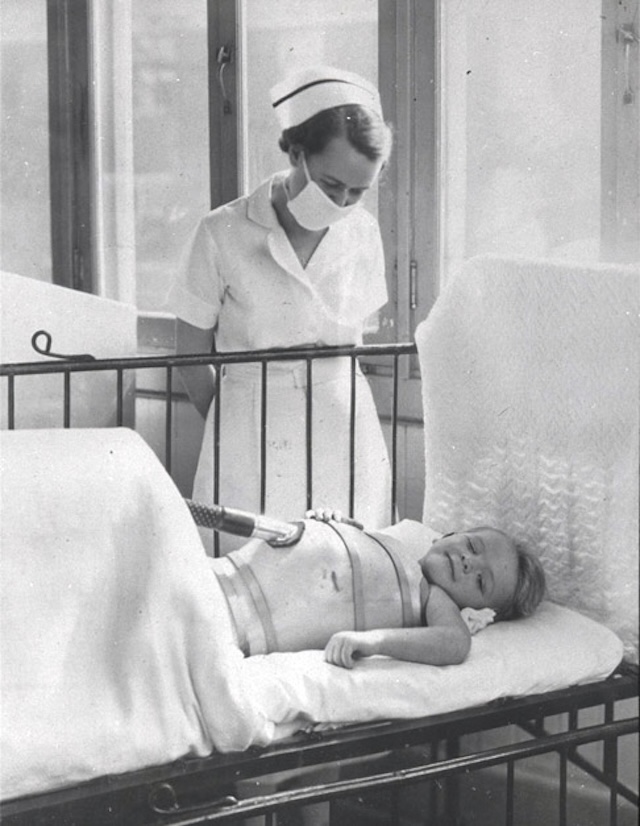

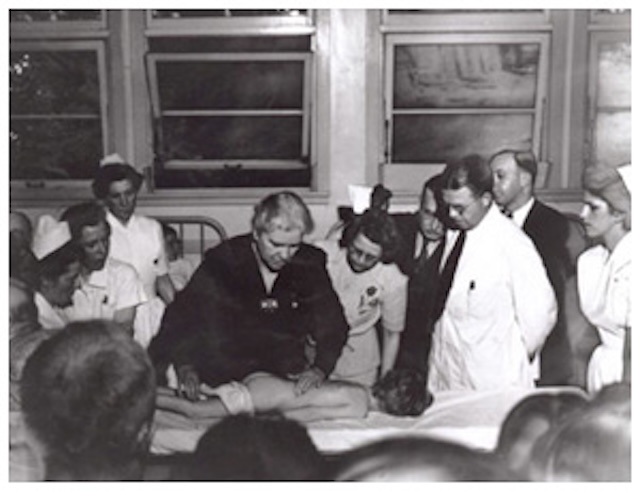

No two cases of polio are the same. The severity of the disease and the areas of the spinal cord it affects vary widely, meaning that the effects of polio are highly individual. Some individuals may experience only mild weakness in their limbs, while others suffer complete paralysis. For many, polio’s effects are lifelong, leading to a lifetime of rehabilitation and physical therapy.

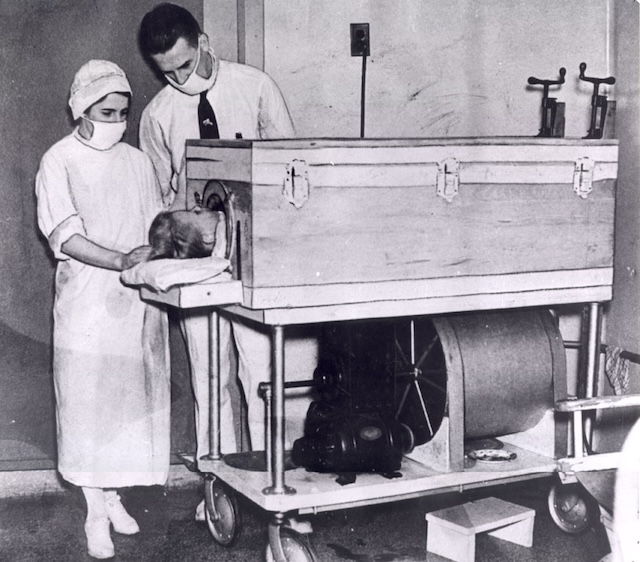

One poignant story is that of Gordon Jackson, who contracted polio in 1937 during a major epidemic in Toronto. At just four years old, Gordon’s limbs became paralyzed, and his breathing was severely affected. With only one iron lung available at the hospital, Gordon’s case illustrated the rapid progression of polio and the desperate measures taken to save lives. A team of engineers and carpenters worked tirelessly to build a makeshift wooden lung to assist his breathing, saving his life. Eventually, Gordon was able to use a more advanced iron lung, and after several months of recovery, he was able to leave the hospital.

Jeannette Shannon’s experience in 1947 was equally harrowing. At the age of 11, she contracted polio, which left her completely paralyzed. Jeannette spent months in isolation, enduring not only the disease’s physical toll but also the emotional burden of being cut off from her family. After years of physiotherapy, she eventually regained her ability to walk and lead a normal life, although post-polio syndrome returned to cause her pain decades later.

The stories of Neil Young and Joni Mitchell, both of whom contracted polio in their youth, are also memorable. Neil Young, who contracted polio at age 5, recalls the painful experience and the emotional toll it took on him. Similarly, Joni Mitchell described how the disease prematurely forced her into adulthood, leaving her with lasting physical and emotional scars.

Polio in Canada: The Struggle to Control the Epidemic

Polio first began to make headlines in Canada in 1910, when several outbreaks affected children and adults alike. The virus spread rapidly, with devastating results. In 1916, a massive polio epidemic in the northeastern United States spilled over into Canada, leading to widespread panic and travel restrictions.

A turning point in the history of polio came in 1921 when Franklin D. Roosevelt, who would later become the President of the United States, contracted the disease. His high-profile case brought attention to polio and its potential to cripple even the most powerful individuals. In response to this, Roosevelt founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, which launched the famous “March of Dimes” fundraising campaigns to support research and aid victims.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, polio epidemics continued to wreak havoc across Canada. Provinces such as Ontario, Manitoba, and Quebec were hit particularly hard. Hospitals struggled to cope with the influx of polio patients, and new measures were introduced to combat the disease, including the widespread use of the iron lung, a machine that helped patients breathe when their respiratory muscles were paralyzed.

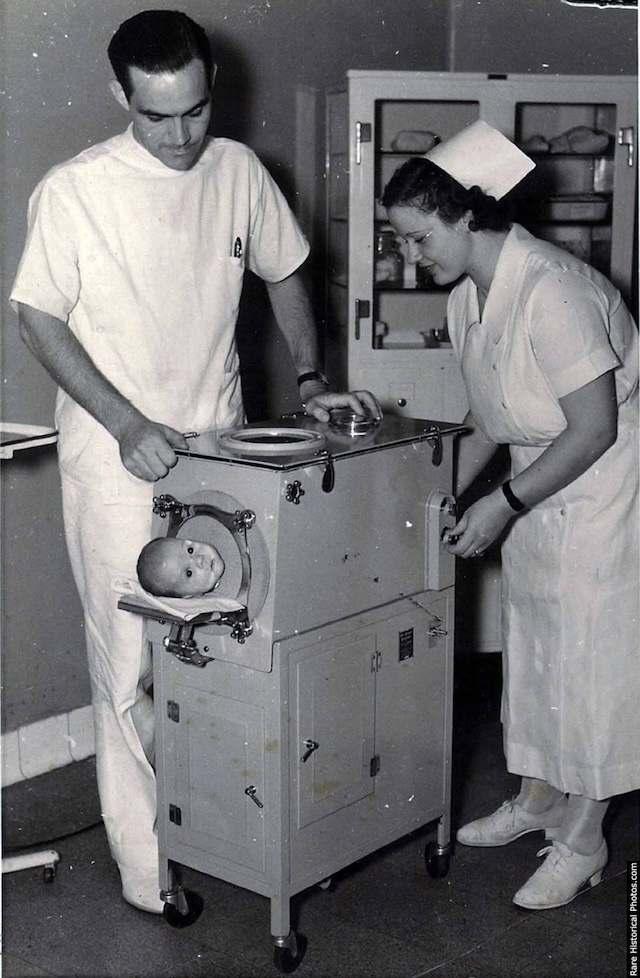

The Iron Lung: A Lifeline for Polio Victims

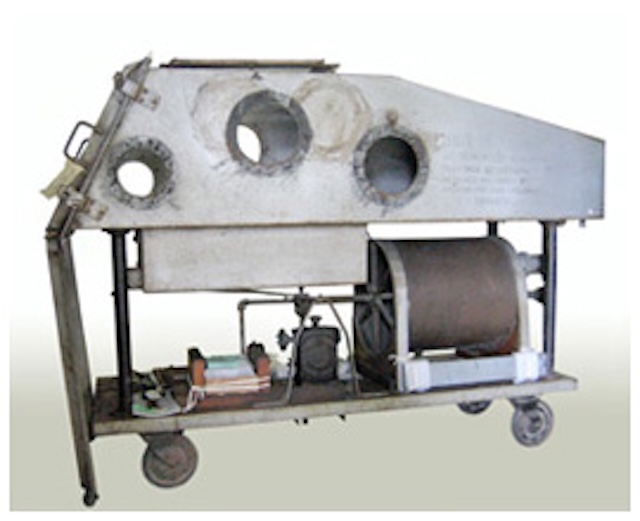

The iron lung became a symbol of the battle against polio in the early 20th century. Invented in 1928, the machine used negative pressure to help patients breathe when their chest muscles were paralyzed. It was a bulky, expensive device, but it saved thousands of lives during the polio epidemics.

The iron lung worked by creating a partial vacuum around the patient’s body, causing their chest to expand and contract as if they were breathing naturally. Although the machine helped patients survive, it was not without drawbacks. The iron lung was large, costly, and could only be used to assist with breathing. Patients often spent months, or even years, trapped inside these machines, unable to move or lead a normal life.

Despite its limitations, the iron lung saved many lives, and its use continued until the development of more modern ventilators in the 1950s. Today, the iron lung is a relic of medical history, replaced by more efficient and less invasive methods of respiratory support.

The Search for a Polio Vaccine: Breakthroughs and Challenges

The quest for a polio vaccine was a long and challenging journey. Though the poliovirus was first isolated in 1908, researchers struggled for decades to understand how it spread and how it could be prevented. In the 1930s, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis helped fund research into a polio vaccine, leading to significant advances in the field.

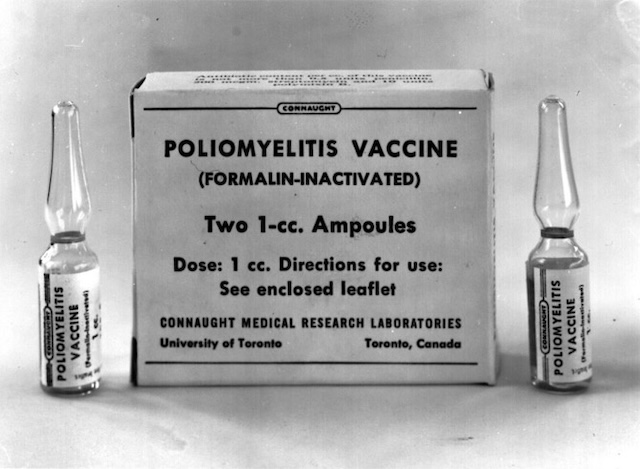

One of the key breakthroughs came in 1952 when Dr. Jonas Salk developed an inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) that could be safely tested on children. This marked a turning point in the fight against polio. A massive field trial in 1954, involving over a million children, confirmed that the vaccine was both safe and effective. By 1955, the Salk vaccine was available to the public, dramatically reducing the number of polio cases worldwide.

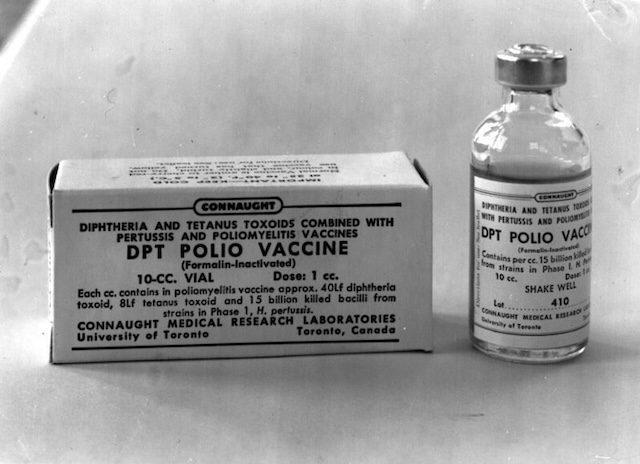

In the years that followed, a second polio vaccine, developed by Dr. Albert Sabin, was introduced. Unlike the IPV, Sabin’s oral polio vaccine (OPV) used a weakened form of the virus and could be taken in a simple oral dose. The OPV became the preferred method of vaccination in many countries, and polio incidence began to decline dramatically.

Polio Eradication and the Global Campaign

The success of the Salk and Sabin vaccines led to a dramatic reduction in polio cases worldwide. By 1962, the United States had seen a 99% decrease in polio cases, and the global push to eradicate the disease began in earnest.

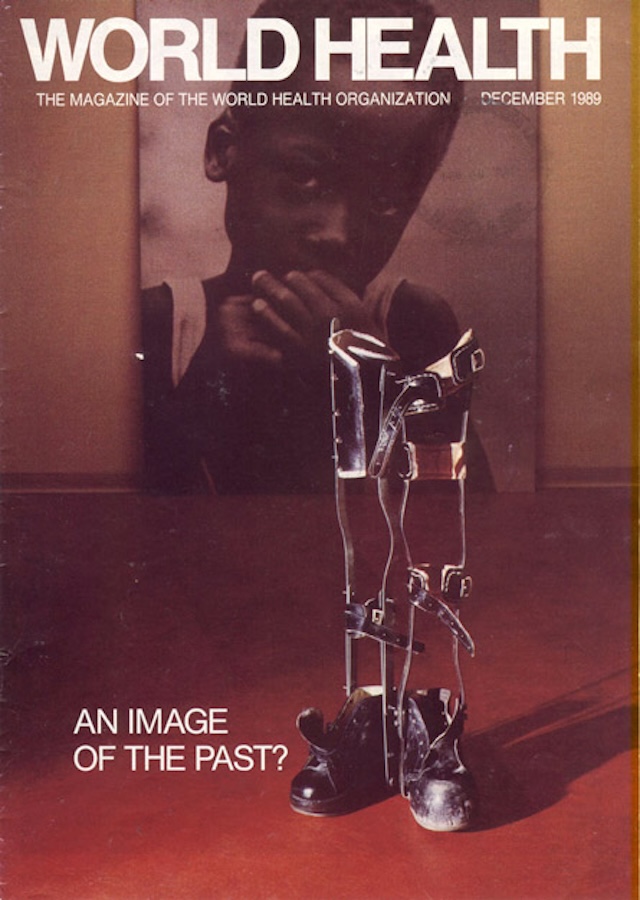

The World Health Organization launched its global polio eradication campaign in 1988, with the goal of eliminating the disease once and for all. Since then, significant progress has been made. By the 1990s, polio was virtually eradicated in most parts of the world, with only a few countries still reporting cases. Today, the disease is endemic in just three countries: Nigeria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

Despite the progress, challenges remain. Political instability in certain regions, along with logistical difficulties, has slowed the eradication efforts. Nevertheless, the polio story is far from over, and continued vigilance and vaccination efforts are necessary to ensure the disease is eradicated completely.

The Legacy of Polio

Polio’s legacy is one of both tragedy and triumph. While the disease caused immeasurable suffering for millions of people, the development of vaccines has saved countless lives and prevented further devastation. The story of polio serves as a reminder of the importance of medical research, global collaboration, and the relentless pursuit of progress in the fight against infectious diseases.

As the world continues its fight against polio, the legacy of this once-feared disease will live on, shaping our understanding of public health, medical innovation, and the importance of vaccination. The journey to eradicate polio may not be over, but the progress made so far is a testament to the resilience of the global community.

Video

Check out this video on Conquering the Polio Epidemic. Watch to learn how medical advancements helped overcome this global health crisis.